The Strategy Pattern

When designing a dynamic system that has to behave in different ways for different situations, it’s very tempting to cram the behavior for all possible scenarios into one class, and trigger those behaviors with a basic conditional or case statement.

While it may not look that bad immediately, you must resist this temptation or run the risk of that single class becoming a gigantic mess of code that is hard to read, test, and maintain.

I recently ran into this situation while creating a tic-tac-toe game that has an AI with three different difficulty levels. My first approach was to create a method for each of the difficulties, and then call each one based on a String that represented the users selection. The example below shows a watered down version of the Ai class that I created, and the difficulty mode methods.

class Ai implements IPlayer {

private String difficulty;

public Ai(String difficulty) {

this.difficulty = difficulty;

}

public void easyMode(Board board) { /* easy logic */ }

public void mediumMode(Board board) { /* medium logic */ }

public void hardMode(Board board) { /* hard logic */ }

void makeMove(Board board) {

if (difficulty.equals("Easy")) {

easyMode(board);

}

if (difficulty.equals("Medium")) {

mediumMode(board);

}

if (difficulty.equals("Hard")) {

hardMode(board);

}

}

}

This situation occurs often enough when creating software, that developers have created recommendations for combating this behavior. The one we’re going to be looking at in this post is called the strategy pattern.

What is the strategy pattern

Design Patterns, defines the strategy pattern as:

a way of creating objects that represent various strategies, and a context object who’s behavior varies as per it’s strategy object.

The strategy pattern is great to use when you have related classes that only differ in their behavior, a class that defines many behaviors (often manifested as conditional logic), or you need different variations of an algorithm depending on different context.

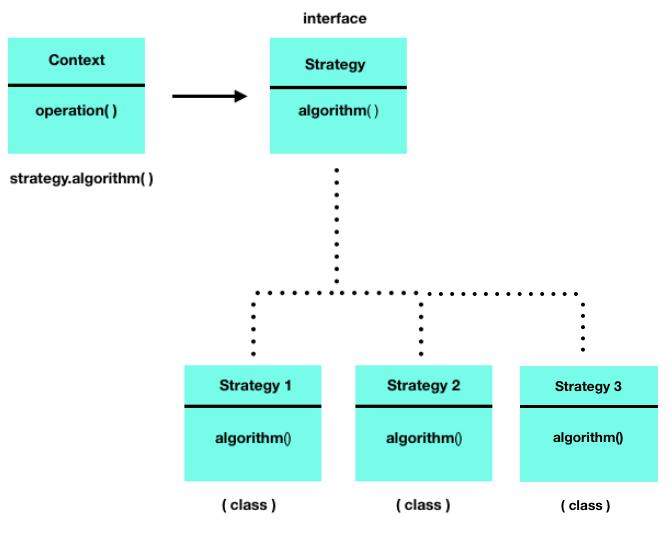

Let’s break down that definition with a diagram, and then see if we can refactor the example from above.

The context in this diagram represents the location where the algorithm will be used, and is where any arguments will be passed in order for it to work.

public void makeMove(IBoard board) {

difficulty.markBoard(board);

}

The strategy interface is responsible for defining a contract that all classes implementing it should follow. The strategy interface will be fairly simple but immensely important because it allows us to create different concrete classes that we can select at runtime.

public interface IStrategy {

void markBoard(IBoard board);

}

Finally our three strategies. Each of these strategies implements the IStrategy interface, so the methods within will obey what ever contract we have defined. These are the concrete classes that I mentioned above. Each holds a unique implementation of the markBoard method.

public class EasyDifficulty implements IStrategy {

public void markBoard(Board board) { /* unique logic */ }

}

public class MediumDifficulty implements IStrategy {

public void markBoard(Board board) { /* unique logic */ }

}

public class HardDifficulty implements IStrategy {

public void markBoard(Board board) { /* unique logic */ }

}

A fully refactored version of the first example would look like this:

public class Ai implements IPlayer {

private IStrategy difficulty;

public Ai(IStrategy difficulty) {

this.difficulty = difficulty;

}

public void makeMove(IBoard board) {

difficulty.markBoard(board);

}

}

Look at how much smaller and cleaner the Ai class has become! We were able to get rid of the ugly conditional statements and replace them with a strategy that has been provided with the context it needs to run. Each of the difficulty levels have their own logic that live in separate classes, so we were able to remove the easyMode, mediumMode, and hardMode method definitions as well.

Summary

Using the strategy patten can make your code easier to read, maintain, and modify. It allows you to remove clutter from classes and helps to keep the number of responsibilities in each class to a minimum.